November 11, 2018 marked the hundredth anniversary of the Armistice that ended the War to end all wars. Although far from the battlefields, many Sandy Hill residents were profoundly affected by this war. Memorials in several Sandy Hill churches and the University of Ottawa list the names of the men who served and died. At the former All Saints Anglican church, the names of 19 parishioners who sacrificed their lives are recorded on a memorial plaque. Similar plaques can be found at St Joseph’s (353 parishioners enlisted, 31 died), St Alban’s (93 enlisted and 8 deaths) and St Paul Eastern (a combined 187 enlisted and 22 fatalities for the St Paul Presbyterian and Eastern Methodist churches).

Not all were Sandy Hill residents, of course, but many of them were: they listed their addresses on Besserer, Henderson, Waller, Rideau, Nicholas, Cumberland, King Edward, Somerset… . The dead included the sons of prominent local residents, such as John McGee, the recently-retired clerk of the Privy Council (185 Daly Ave.) who lost two sons at the front, and had a third wounded, and James Woods, a leading businessman and philanthropist (323 Chapel St.) who lost a son at the Battle of the Somme. But most of those who died came from ordinary families. Thanks to their medical examination at enlistment, we have some idea of what they looked like. We also know where their next of kin lived (usually parents or wife), whether they had children, their previous employment, if any, when they were shipped to England and then France, their regiment and service record, their pay, where and when they died and where they are buried (or remembered for those whose body was never found)[1].

But in most cases, we do not know who they really had been, whether they had led happy lives, whether they had left a girlfriend behind or what they had aspired to become had the War not intervened. We can only guess at what they lived through while at the front and how the news of their death affected their loved ones back home.

Source: Saint-Paul University archives. AUO-NEG-NB-38A-2-439; AUO-PHO-NB-38A-2-439.

Those who did not serve were also affected by the War. Fuel shortages forced the St Paul Presbyterian and the Eastern Methodist churches to hold joint services during the cold season (the two churches would later merge). The career of architect Francis Sullivan, who lived at 346 Somerset E., took a turn for the worse when commissions dried up because of the War. Broke, he had to give up his house. In 1917, he designed a few military hospitals but left Ottawa the following year, never to return. James Woods’ business, however, thrived as he supplied tents and other military supplies to the Canadian army, including its first gas masks.

The War also gave rise to extraordinary philanthropic efforts. Lillian Freiman (née Bilsky), who grew up in Sandy Hill before moving to Somerset St. W., led sewing circles for the Red Cross in her living room, raised funds for displaced refugees and helped found the Great War Veterans’ Association of Canada (later the Canadian Legion). After the War, she raised funds for veterans’ organizations, headed Canada’s first Poppy Day campaign and went on to become affectionately known as the “Poppy Lady”. Almanda Marchand, one of whose sons was captured in combat, founded the Fédération des femmes canadiennes françaises to aid the war effort and organized volunteers to prepare care packages to be sent to the front. Mme Marchand stored these in the attic of her house at 240 Charlotte St.

Sir Robert Borden was Canada’s prime minister through the War, living on Wurtemburg St. just across Rideau St. In the summer of 1917, he agonized over the deep divisions between French and English created by the conscription crisis and sought to create a union government with the Opposition Liberals led by Sir Wilfrid Laurier, who of course lived at 335 Laurier Ave. E. When Laurier refused (he opposed conscription), Borden considered resigning and asking the Governor General to name another Sandy Hill resident and member of the Supreme Court as interim prime minister, the Hon. Lyman Duff, (Duff lived at 30 Goulburn Ave. at the time). Conservative colleagues talked Borden out of resigning and he won the general election in the Fall. Sandy Hill may have been far from the front but decisions on who would lead our country through one of its darkest hours involved three of our well-known residents.

World War 1 was a tragedy for the Sandy Hill families who lost their loved ones but it did not materially change the fabric of the neighbourhood. World War 2 did. It had a profound and lasting impact, mostly in the conversion of former private homes into offices, diplomatic missions or barracks. Once converted, these homes did not return to their former residential use when the War ended. The War thus cemented a slow transformation in Sandy Hill that had already begun earlier, from a largely upper class neighbourhood distinguished by large mansions, into a mixed neighbourhood featuring smaller houses, higher density and a greater institutional footprint.

Three major factors accounted for this transformation. First, Sandy Hill acquired a noticeable military presence in the second half of the War, particularly along Laurier Ave. E.. Several large Sandy Hill mansions were re-purposed to serve the War effort, among them:

- Kildare Annex (now Amnesty International at 312 Laurier Ave.) became a barracks for the Canadian Women’s Army Corps and would house the Canadian Army Provost Corps immediately after the War;

- Bremner House (345 Laurier Ave. E. but now demolished) became the Examination Unit , Canada’s espionage centre;

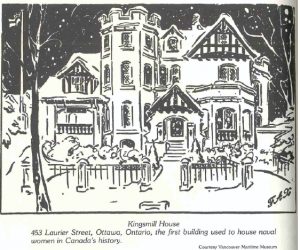

- Munross (formerly the house of James Mather, now the Cordon Bleu at 453 Laurier Ave. E.) was used as a residence for the Women’s Royal Canadian Navy Service and was renamed Kingsmill House in 1942);

- Kildare House (323 Chapel), formerly the home of James Woods, served as barracks during the war;

- Hardy House (now the Polish embassy at 443 Daly Ave.) provided officers’ training for the Women’s Royal Canadian Navy Service.

In addition, the government built the Varsity Oval Barracks on the University of Ottawa’s athletic field south of Somerset St. in 1942. Composed of eight buildings designed to house 400 women of the Canadian Women’s Army Corps,[2] the barracks were sold to the University in 1946 and became classrooms and residences for the new faculties of medicine, engineering and sciences. At least one of these buildings stood until 1972.

In addition, the government built the Varsity Oval Barracks on the University of Ottawa’s athletic field south of Somerset St. in 1942. Composed of eight buildings designed to house 400 women of the Canadian Women’s Army Corps,[2] the barracks were sold to the University in 1946 and became classrooms and residences for the new faculties of medicine, engineering and sciences. At least one of these buildings stood until 1972.

This photo, taken in the mid-1950s, shows some of the barracks built on the University athletic oval ten years earlier for the Canadian Women’s Army Corps. Note the residential area in the background (Somerset St. and King Edward Ave.?)

A second change to Sandy Hill as a result of the War arose from Canada’s increasing international importance. This new status led more countries to open diplomatic missions in Ottawa[3], several of which were in Sandy Hill: the Soviet government acquired the former Booth house at 285 Charlotte St. in 1943; the Australian High Commission replaced the German consulate at 407 Wilbrod St. in 1940; the Royal Norwegian Legation was housed at 192 Daly Ave.; the Free French government opened a mission at 464 Wilbrod St. The Belgian government moved from a more modest address to Stadacona Hall on Laurier Ave. after the War.

The third change arose from the huge backlog in residential construction that had accumulated as a result of the Great Depression and the War, and the need to accommodate returning veterans. While the post-War construction boom was Canada-wide, in Sandy Hill, it was most evident in building up Strathcona Heights which until then had stood largely empty.

These, of course, were not the War’s only lasting impacts on Sandy Hill. As the memorials in our churches and at the University remind us, several Sandy Hill men died at war, including 9 from St Alban’s, 16 from All Saints and others from St Joseph’s. In addition, 69 University of Ottawa students or graduates (not all from Sandy Hill) perished in the War.

Source: University of Ottawa Archives

Daily life, of course, was also profoundly affected by the War. Rationing and war-induced shortages reduced the variety of goods and food available to all. An indication of the collective belt-tightening is that the number of private cars on Ottawa’s roads fell by 13 per cent during the War even as the city’s population grew by 17 per cent[4]. All media were dominated by War news. Drives to collect blood for the Red Cross, sell Victory bonds or collect metals for recycling were frequent. In politics, the conscription crisis split the country along linguistic lines as it had in 1917. These changes, however, were temporary and life returned to normal as war-time restrictions were gradually lifted.

But it did not return to what it had been pre-war. In September 1945, Igor Gouzenko walked out of the Soviet embassy on Charlotte St. carrying documents revealing the existence of a Soviet spy ring in Canada, kicking off a new Cold War between the West and the Soviet Union. One of the persons he denounced lived in Sandy Hill and was jailed.

More broadly, Ottawa emerged transformed by the War. The size of the federal civil service in Ottawa tripled between 1939 and 1945 (from 12,000 to 36,000), turning Ottawa from an industrial into a government town, and increasing the demand for professional housing downtown. After the War, the Dutch government gave Ottawa 100,000 tulip bulbs to thank the City for having sheltered its royal family, giving rise to our much-beloved annual Tulip Festival. Its best-known photographer (and co-founder) was Malak Karsh, who for five years lived at the corner of Laurier and Russell Aves.

Sources

[1] Terry Byrne’s short biographical capsules of each of St Joseph’s parishioners who died at war that can be seen in the church’s vestibule. More information is available on-line at the Library and Archives Canada website.

[2] One can watch a 1944 two-minute National Film Board recruiting video for the Canadian Women’s Army Corps at https://www.nfb.ca/film/proudest_girl_in_world/

[3] There were 6 foreign legations in Ottawa in 1940 and 19 in 1945.

[4] The number of private automobiles fell from 21,583 to 19,087 between 1941 and 1946 while the population of “greater Ottawa” grew from 181,506 in 1940 to 220, 026 in 1946 (Source : City Directories).